The History

Gateway Bank, located at 3412 N. Union Boulevard, was established in 1965 as the first and only minority-owned commercial bank in Missouri. It took local deposits and made loans in a neighborhood where few other banks focused.

In 2009, Gateway Bank was acquired by Central Bank of Kansas City where it operated until 2012. During that time, St. Louis was the third highest underbanked African-American community in the U.S. according to the FDIC.

In 2012, St. Louis Community Credit Union announced plans to save Gateway by purchasing the existing land. With the help of additional funding from a Community Development Block Grant, as well as support from the City of St. Louis, Stifel Bank & Trust, the St. Louis City NAACP, TIAA Direct and others, St. Louis Community Credit Union is building a new state-of-the art facility on the original site, while still preserving the great heritage of Gateway Bank. The new location will be called the St. Louis Community Credit Union Gateway Branch. It opened in March 2016.

The Gateway Story

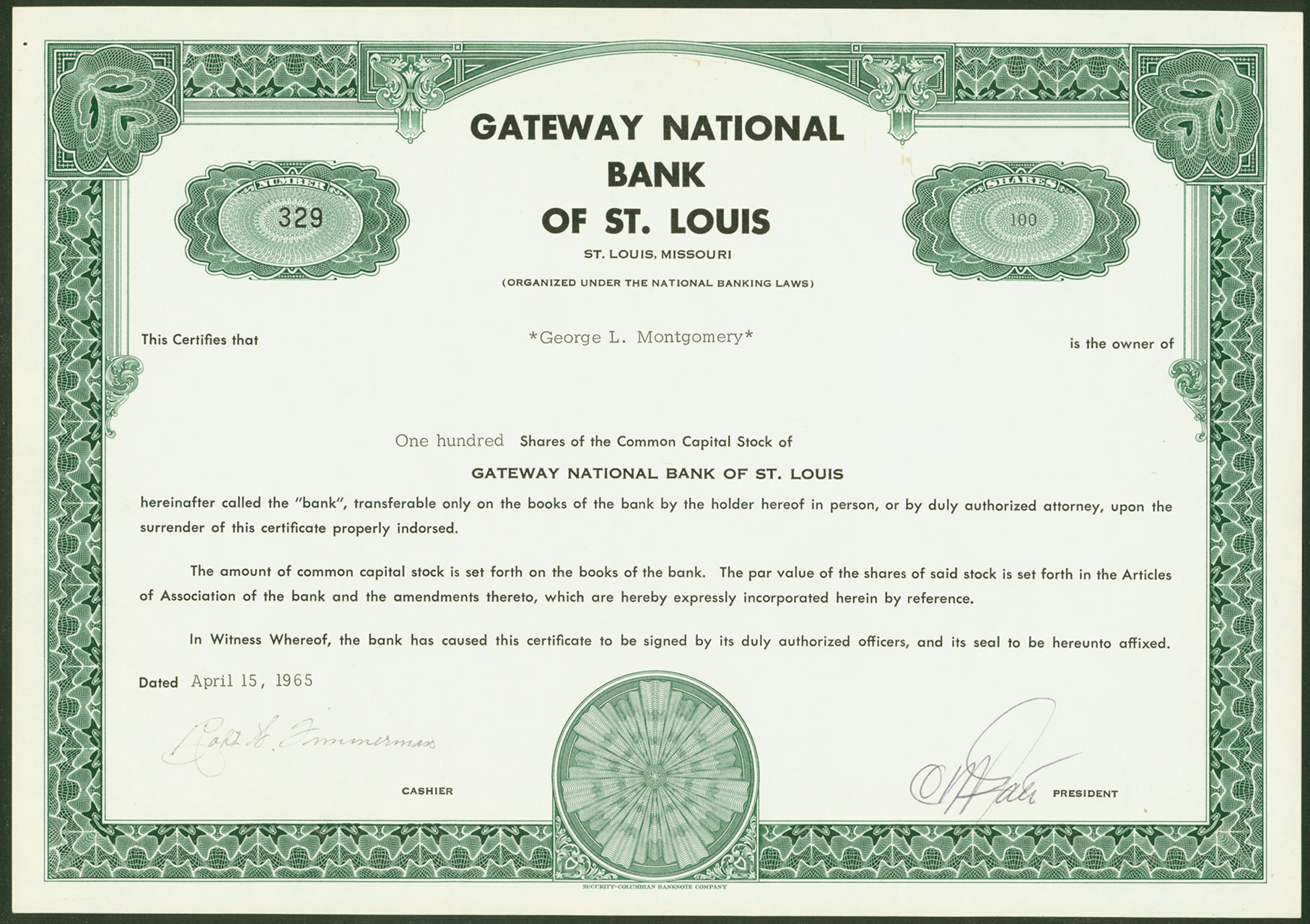

Chartered in 1965, plans for Gateway began in 1961 when businessman George L. Montgomery (details below) began to talk with friends and business colleagues about the need for a minority-owned, full-service bank. Though two black-owned financial institutions had been established earlier in St. Louis – New Age Building and Loan Association (chartered in 1915) and People’s Loan and Finance Company (chartered 1923), these were not full-service commercial banks.1

Gateway Bank President Clifton W. Gates (left) and Board Member Tom Jones (right) review construction plans in front of the new bank in 1965. Courtesy St. Louis Community Credit Union / Lisa Gates Collection.

Black-owned banking institutions emerged in the United States after the Civil War, established primarily by “fraternal orders and black churches” during Reconstruction. Gateway National Bank was a relatively early effort in terms of the nation’s black-owned national (commercial) banks, which had been slow to progress in the western United States. The earliest black-owned bank in the Midwest was Douglass State Bank of Kansas City (KS), chartered in 1947. Most black-owned banks were “short-lived, from five to fifteen years.”2 Gateway was an exception, retaining its minority-owned association until 2001. Although ownership and investors changed at that time, the bank continued to retain a largely African-American staff and shareholder status until it closed in 2012.3

Trailblazers: Gateway’s Founders

Many individuals attribute Gateway National Bank’s origination to the 1963 Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) demonstrations at Jefferson Bank in downtown St. Louis, but this was not the case. The individuals behind Gateway’s origination, as well as their neighbors, families and friends were well aware that St. Louis offered few to no alternatives when it came to equal opportunities.

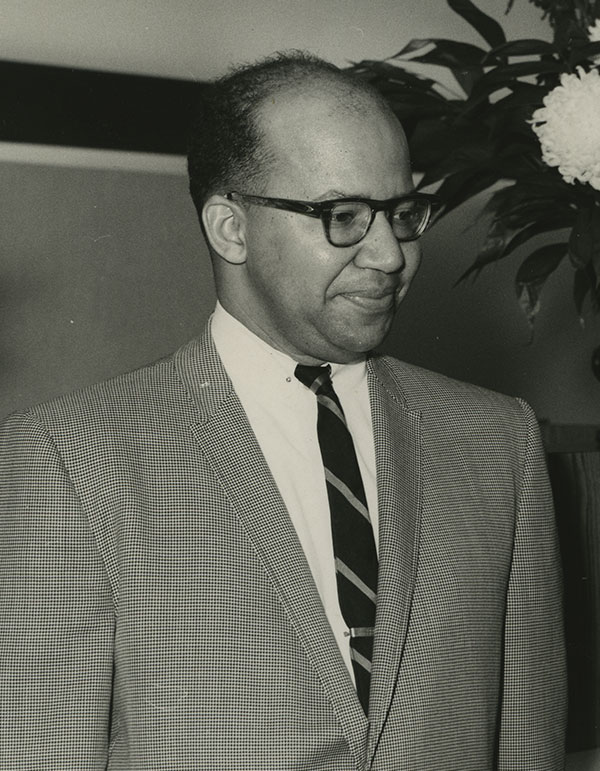

Without equal banking access, African Americans could not get loans to buy homes or start businesses, nor would white-owned banks hire blacks for jobs beyond those associated with menial labor.4 Gateway National Bank was a simple but nearly unattainable solution for the countless problems presented to blacks because of segregation laws and restrictive covenants. The main force behind Gateway’s origination was not the charge led by CORE, however, but an individual, George Louis Montgomery, Jr. (1934 – 2014).5

Montgomery was a native St. Louisan. He attended Vashon High School and went on to earn a degree in commerce from Saint Louis University in 1955, studying real estate at Washington University after that time. In 1961, Montgomery attended a black businessman’s meeting at the Statler-Hilton Hotel in downtown St. Louis. It was here that he met James H. Browne, President of The Crusader Life Insurance Company and a board member of Douglass State Bank. Browne and Montgomery discussed the possibility of opening a black-owned bank in St. Louis at that time, and both men stayed in touch. In the meantime, Montgomery met with his colleagues every Sunday, at his home. The group dubbed itself the St. Louis Bank Development Association – a “young, energetic and idealistic” group of men “driven” by the need for a black-owned bank in St. Louis. These individuals were well known to one another. Most grew up in the same neighborhoods and attended high school at either Vashon or Sumner – the city’s two black high schools at the time.

A large percentage of Gateway’s founders and board members held higher degrees – several were medical doctors; one was a dentist; others had backgrounds in business, real estate and/or finance.

Original Board of Directors

Gateway National Bank

Gateway National Bank, Board of Directors, left to right: Clyde Cahill, Dr. John Jackson, Leo Bohanon, Melvyn Harrington, Tom Jones, Dr. Benjamin Davis, Clifton Gates, James Harding, Dr. Jerome Williams, Sr., George Montgomery, James Hurt and James Clark (Photo Courtesy of St. Louis Community Credit Union / Lisa Gates Collection).

Original Directors' and Founders' DetailsTrailblazers, continued…

In 1963, Montgomery contacted Browne to set up a meeting in Kansas City between the St. Louis Bank Development Association and associates of Douglass State Bank. The meeting was intended to discuss opening a black-owned bank in St. Louis that could provide “all of the . . . services of existing banks as well as trust services.”8

Montgomery and his associates who traveled to Kansas City consisted “of a Registered Stock Representative, Funeral Director, Accountant, Real Estate Brokers, Insurance Representative, Architect and Sales Representative.”9 These men met with Browne, H.W. Sewing, founder/President of Douglass State Bank and Edward E. Tillmon, Executive Vice-President of Douglass State Bank.10 Tillmon visited St. Louis many times thereafter, assisting Gateway’s founders in setting up bank operations and serving as an original board member of the new bank.11 Other than Dagen and Tureen, who were Jewish, all of Gateway’s original board members were African-American. Board members agreed to raise a minimum of $500,000 capital to open the bank, donating at least $100 of their personal funds (through stock purchases) to further that effort.12

In March 1964, George Montgomery, Leo Bohanon and Melvyn Harrington presented a feasibility study to the regional Chief National Bank Examiner, supporting their case for opening a black-owned bank in St. Louis. The city’s African-American population had expanded significantly since New Age Savings and Loan opened in 1915 – from 9% to 30%.

It was projected that by 1970, 43% of the city’s population would be composed of African Americans. Income was on the rise for blacks as well, though many barriers persisted. Blacks paid more interest for loans than did whites, and the lack of a black-owned bank stifled growth in the African-American community.

Numbers, comparative data and projections were compiled and presented in the feasibility study, which revealed the proposed site for the new bank as 3412 N. Union Boulevard. An existing building on the lot was to be used as the bank, previously a union hall for the United Automobile Workers Local No. 25.13 The location was ideal, situated in the heart of a growing black-business sector near the intersection of Natural Bridge Avenue and N. Union Boulevard.14 Former board member George Carper indicated that during his years at Gateway Bank in the 1970s, businesses in and around the bank (many of which were Gateway depositors) included doctors’ and dentists’ offices, a liquor store and the Chevrolet factory.15 The area was thriving, and so did Gateway National Bank during these years.

By the time the bank’s charter was approved in 1965, plans for the bank were well underway. A young African-American architect, Charles Edward Fleming, was selected to modernize the labor hall for the bank’s use. When the building was demolished in 2015, it appeared much as it had when the bank opened in 1965.

The Early Years

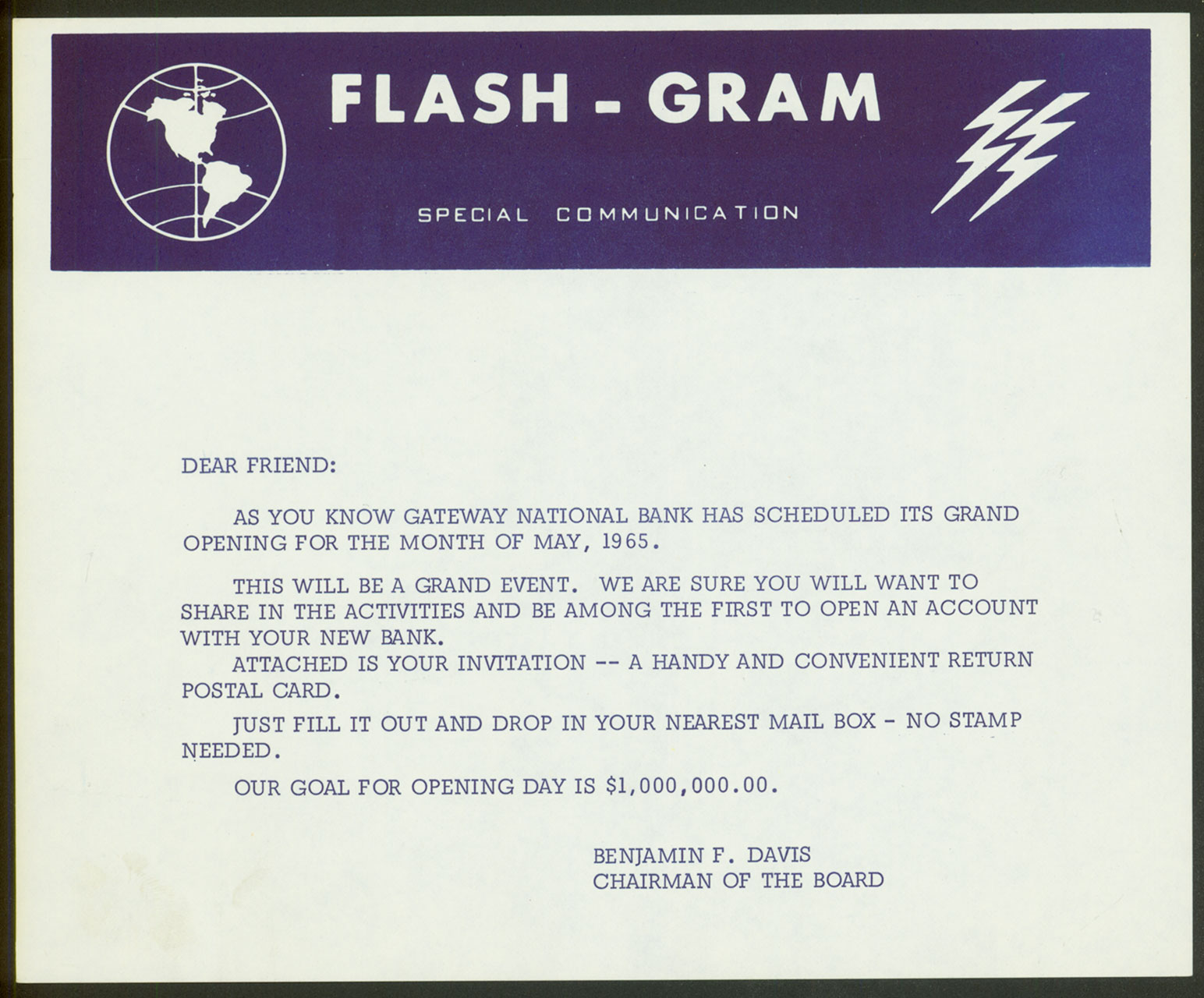

On Sunday, June 27, 1965, Gateway National Bank held its opening celebration. The remodeled building provided walk-up and drive-through banking facilities. A full range of services were offered, including checking and savings accounts, certificates of deposit, safe deposit boxes, and loans. “A series of small business seminars to aid businessmen in the preparation and analysis of financial statements” were offered to the public, as well as evening and weekend banking hours – something that few banks offered at the time – Gateway was one of the first.16 Despite the overall excitement about the bank and its association with the African-American community, many remained skeptical about the Gateway’s viability. A number of residents surveyed prior to the bank’s opening indicated that they were “afraid” the bank would not survive.17 It took time, but eventually the community realized that Gateway Bank could – and did – offer services that other banks failed to provide for African Americans.18

The educational aspect of Gateway National Bank cannot be overstated. Not only did the bank educate customers about fiscal responsibility, Gateway also served as an “incubator” for black professionals.19 When the bank opened, there were few employees who held any experience related to financial institutions because white banks did not hire blacks for such positions, not even as tellers.20 As a retail bank, Gateway literally had thousands of customers – most came to the bank on a regular basis, which made for a personal experience few banks offered.21

Gateway’s first year ended with disappointing results when less than half the board’s anticipated deposits materialized and capital dropped from $500,000 to $385,000. In reaction, an advisory board composed “of 17 clergymen, businessmen and civic leaders” was created, and the board engaged in heavy solicitation of attracting larger businesses as depositors.22 At about the same time, Thomas Jones, Executive Vice-President, returned to New York to accept a financial counseling position.23 Jones’ replacement was an individual who served Gateway well, I. Owen Funderburg (1924-2002). Funderburg came to St. Louis from Mechanics and Farmers Bank of Durham, North Carolina – the nation’s second largest black bank in 1966.24 Born and raised in Georgia, Funderburg held a Business Administration degree from Morehouse College and began working at Farmers & Mechanics following his graduation in 1948. He completed a graduate degree at Rutgers in 1959, returned to work at Farmers & Mechanics, and was employed as a cashier when he accepted the job at Gateway.25

Within two years of Funderburg’s arrival as Gateway’s Executive Vice-President and Chief Executive Office (CEO), the bank earned its first profit. By this time, the bank had attracted a larger percentage of St. Louis’ African-American population as depositors, including “professional individuals such as doctors and lawyers.”26 Business deposits had also grown in numbers and size. This continued steadily throughout the 1960s-1970s as the bank became increasingly trusted by the community. One of the bank’s largest depositors was General Motors, which employed more than 35,000 individuals (many of whom were African-American) at its factory on Natural Bridge Road.27 Another was a hospital administrator and part-time car salesman, Al Johnson. Johnson later moved to Chicago to open General Motors’ first black-owned auto dealership and ultimately became a multi-millionaire.28

As indicated, Gateway Bank had a steady rise in its customers and depositors through the 1970s. Even so, Funderburg noted that “black banks generally face sharper problems in certain areas than other banks do, specifically in their shortage of skilled management, their lack of ‘prime’ business customers, and heavy loan losses.”29 Under Funderburg’s guidance, Gateway National Bank’s “assets grew from $2.5 million to $21 million.”30 Unfortunately, Funderburg left Gateway in 1974 to accept the position of President and Chief Executive Officer at Citizens Trust in Atlanta (Georgia).31 By the time Funderburg retired from Citizens in 1991, that institution was the nation’s second-largest black-owned bank with assets of $115 million.32

Another of Gateway Bank’s original directors, who left to successfully pursue other alternative banking careers, was Melvyn A. Harrington. Harrington had been instrumental in gaining Gateway’s initial correspondent bank, First National Bank. Correspondent banks were necessary for smaller banks like Gateway to clear their daily deposits. Harrington’s ability to secure a large white-owned bank as a correspondent was a great accomplishment that was noticed by others. His reputation led to an offer from New Age Savings & Loan in 1970, which Harrington accepted as Executive Officer. Following New Age, Harrington worked as a loan officer at UMB in downtown St. Louis.

Trying Times

By the 1980s, there were signs of trouble at Gateway National Bank. The decade landed “a pile of problem loans that threatened to sink” [the bank] and federal bank regulators stepped in to temporarily oversee operations. Clifton Gates left in 1987, but returned to the board in 1989. By the mid-1990s, he was the bank’s largest shareholder. Clifton Gates “was very dedicated to the African-American community and he had a passion for serving the community.” He was among the bank’s first investors and an original board member, accomplishing much in his lifetime. Gates was St. Louis’ first African-American appointed to the Board of Police Commissioners and proprietor of Lismark Distributing Company (1975-1992), one of the nation’s largest black-owned businesses. In good times and in bad, Gates stood by the reputation of Gateway National Bank, working diligently to grow the bank’s success during his 40-plus years at Gateway.

Though Gateway National Bank weathered the 1980s, bad times continued. The situation was not novel – black banks across the nation were in trouble.

“In 1992, the [nation’s] 36 black banks had total assets of $2 billion dollars – out of all American assets of $3.5 trillion dollars.” These statistics did not improve, which made minority banking even more challenging over the years. In 2001, Gateway was purchased by an investment group owned by Brian McNamara, which marked the end of Gateway’s association as a black-owned bank. Two years later, McNamara left, encouraged by the board, which had become disillusioned by McNamara’s failure to increase assets. Times remained tough and in 2009, Central Bank of Kansas City purchased Gateway, changing the institution’s name to Central Bank of St. Louis. There were high hopes for Central Bank, which had proven its worth in successfully operating a bank for low-income clients, despite many odds against such an achievement. Unfortunately, the national banking crisis compounded the situation, leading to closure of Gateway/Central Bank of St. Louis in 2012. Minority banks suffered most during the United States’ financial crisis of 2008-2009 as did the communities that they served.

Though Gateway National Bank weathered the 1980s, bad times continued. The situation was not novel – black banks across the nation were in trouble.

Hope on the Horizon

In 2012, St. Louis Community Credit Union announced plans to save Gateway Bank by purchasing the existing land. The building was demolished in 2015. With the help of additional funding from a Community Development Block Grant, as well as support from the City of St. Louis, Stifel Bank & Trust, the St. Louis City NAACP, TIAA Direct

and others, St. Louis Community Credit Union built a new state-of-the art facility on the original site, while still preserving the great heritage of Gateway Bank.

Many of Gateway’s traditions continue in the new financial institution. It opened in March 2016.

Gateway’s Community Impact

Gateway Bank had a tremendous impact on the community and those it served. Hear from past employees, community leaders and family members on the significance of Gateway Bank.

- Russell Little, Sr.

Former Gateway ShareholderView Transcript - Barbara Harness

Former Gateway SVP OperationsView Transcript - Michael McMillan

President & CEO, Urban League Metropolitan St. Louis

(nephew of Col. Clifton Gates, Chairman Emeritus, Gateway Bank)View Transcript - Thomas L. Mines

Former Gateway Teller & Loan Officer

View Transcript

- Dr. John A. Wright

Educator/Historian/AuthorView Transcript - Delores Jones

Former Gateway Lead Teller & Loan Officer

Now with St. Louis Community Credit Union

View Transcript - Letrissa Bennett

Former Gateway Teller, Teller Supervisor

Now with St. Louis Community Credit Union

View Transcript - Lisa Gates

Daughter of Col. Clifton Gates, Chairman Emeritus/Founder of Gateway Bank. He passed away in 2007.

View Transcript

About St. Louis Community Credit Union

As a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI), St. Louis Community Credit Union is a full-service financial institution that primarily serves low-to-moderate income individuals living in and around the region’s urban areas. As part of its overall giveback to the community, the Credit Union provides locations in underserved communities, credit building products, second-chance checking accounts, a payday loan alternative and hands-on financial education. These service-minded qualities resemble those of the original Gateway Bank.

Although Gateway was demolished in 2015, the building’s significance and history survive. Many of Gateway’s traditions continue through St. Louis Community Credit Union. Gateway National Bank remains an icon in the African-American community of St. Louis. The bank, its founders and its mission over the years are an enduring testament to those who sought equality in all aspects of life for St. Louis’ African-American community.

On Feb. 29, 2016, we hosted a historic ribbon cutting celebration for the St. Louis Community Credit Union Gateway Branch. More than 100 people attended. Below, watch a video of this special event!

St. Louis Community Credit Union is honored to bring affordable banking services and financial empowerment back to North St. Louis city.

View Preserving the Legacy: SLCCU's Gateway Branch Ribbon Cutting Video Transcript

– ♫ Sometimes in our lives ♫ We all have pain ♫ We all have sorrow ♫ But if we are wise ♫ We know that there’s ♫ Always tomorrow ♫ Lean on me ♫ When you’re not strong ♫ I’ll be your friend

– [Host] Welcome to our official celebration of the St. Louis Community Credit Union Gateway branch. On June 27, 1965, Gateway Bank hosted it’s grand opening celebration right here, on this very site. And now here we are 51 years later. This moment was one of great anticipation for a lot of us. And now the wait is over. We’d like to open our ceremony with a moment of prayer.

– God, our Father, we thank you for this awesome occasion wherein you have gathered a host of partners. We pray your strength upon those who have worked to plant seeds, and now they get to see it come up and flourish. We give you praise for it all, and it’s in Christ’s name we pray. Amen.

– [Guests] Amen.

– [Host] We would not be here today it it weren’t for those who gave before us. They leaned on each other to create something remarkable. ♫ When you need a hand ♫ We all need somebody ♫ To lean on ♫ I just might have a problem ♫ That you understand ♫ We all need somebody to lean on

– You know history is coming full circle today at this new Gateway Branch. We are reclaiming this spot as a beacon of financial reform and economic hope. I have a strong new ally at this credit union branch, and we are going to use it to protect you. We’re gonna use it to help un-bank families get a secure account. We’re going to help people who have bad credit to get on the right path to transforming that with daily financial literacy. And we’re going to encourage people to save for a stable future.

– It is a wonderful facility, and it’s gonna serve as a catalyst to bring other diverse services and business to the community. And it’s a place that both young and old can learn about accomplishing important financial literacy goals. The cost of building a new banking facility, a lot of money. The time it took to get through the paperwork to preserve the historic legacy of the Gateway Branch, a long time. The time it took to get the branch at the St. Louis Community Credit Union Gateway Branch to this location, a very long time. The convenience of my constituents and other residents who live in the various neighborhoods in north St. Louis surrounding communities being able to walk and drive around the corner, instead of driving to the Forest Park, or University City Branch to do their banking, priceless. Thank you.

– One of the things that I enjoy doing most as mayor is just being involved with so many St. Louisons who work together to help create something very important for our community. And that’s what’s happening here. The city is also proud to have contributed $700,000, both in community block rent funds, as well as affordable housing trust funds. I’d also like to take this opportunity to thank the founders of the original Gateway Bank. Your vision and hard work is an example of compassionate capitalism that north St. Louis, and our entire community should be very proud of. The city of St. Louis stands behind you. We are very, very proud of this collaborative effort. We are invested in your success, and our collective success for this.

– My father, being the young visionary that he was decided to establish a minority owned bank. My father would be very proud today. He would be proud that his picture is hanging in that lobby. But he would be most proud that the mission of Gateway National Bank is still in effect today through the St. Louis Community Credit Union. He would be proud to know that Gateway’s traditions will continue through this new financial institution. He would also be proud to know that St. Louis Community Credit Union will continue to provide financial services and various programs to this community.

– When I came to the reception last week, I had a memory of my father going upstairs to the second floor to attend monthly board meetings. Many decisions were made in that room that gave a new beginning to individuals, families, and businesses. I know my father would be very proud to see the legacy of Gateway continue with the same purpose and passion as he and the other founders and investors had. Also while I was here last week, I had the pleasure of seeing the pride, and excitement in the eyes of Melvin Harrington, who was one of Gateway’s original founders. He knows that the vision of those pioneers will carry on.

– In order to raise the bar, you have to work in partnership. In actuality, while I had a chance to play quarterback, it was actually Chris Ryker who caught the ball, and he ran with it. I didn’t know he was a half back, but he took off. You know, working in partnership to make a tangible difference in our community is something all of us can do. It is something that, if you allow it, it would act as a distinction of who you are as an individual.

– TIAA Direct is part of that legacy, that non profit legacy to support these individuals. The TIAA Direct brand is headquartered here in St. Louis, and we were approached by the St. Louis Community Credit Union a few years ago to help support the Gateway Branch. We helped fund the technology in there, we helped support some of the other programs you have going on.

– This branch gives us the opportunity to carry on the Gateway Bank tradition of serving with passion every day. Which I believe is what the Gateway founders intended. It’s passion that drives our existence. We’re passionate about connecting underserved populations with real, helpful, lasting financial solutions. We’re passionate about rebuilding neighborhoods. That passion inspires our staff to come in every day, ready to serve. It drives us to build community partnerships towards a stronger city. It drives us to deliver affordable products and services as well as better ways to reach the population that needs us. The Gateway story lives on through St. Louis Community Credit Union today, tomorrow, and always.

– [Host] Get ready. Five, four, three, two, one,

– All right! All right. ♫ Closer for me ♫ That you won’t let show ♫ Call on my brother ♫ When you need a friend ♫ We all need somebody to lean on ♫ I just might have a problem ♫ That you understand ♫ We all need somebody to lean on ♫ Just call me ♫ When you need a friend ♫ Call me